Cooperstown Centennial

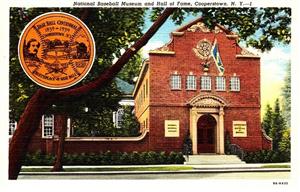

Ford Frick reintroduced Sam Crane’s concept of building a National Baseball Museum and Hall of Fame. This concept expanded Stephen Clark’s vision of a local museum and the Clark Foundation embraced the expansion of the concept. Ford Frick also suggested that a celebration of baseball’s 100th anniversary be considered and that some activity should be planned for 1939. Thus, the Centennial of Baseball was born.

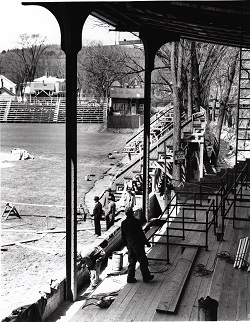

Doubleday Field went through another renovation in 1934. All parties seem to be satisfied with its condition except Ford Frick whose vision of a celebration would include Major League Baseball conducting a ceremonial game there. This required expanded seating and a formal grandstand. Having already renovated the field twice, the community was resistant, but the leaders of the Village convinced the residents of the value of a third renovation. Alexander Cleland was unflappable and met these new challenges with increased vigor and commitment to pull together the community. The national scope of this project certainly aided the WPA decision to support further renovations and reduce frustration of the Village to continue to raise money for a ball field that never seemed to be finished. The Village, concerned about losing its identity and being overrun by Major League Baseball, reached an agreement that Cooperstown’s interests would be protected by the Cooperstown Baseball Centennial Committee which was established early in 1937. All monies accumulated by the Doubleday Field Association were turned over to this committee and all activities by the standing committees would now filter through the Cooperstown Baseball Centennial Committee. Alexander Cleland represented the Cooperstown Baseball Centennial Committee at the meetings of Major League Baseball. This liaison worked well in preserving the interests of the community and, although frustrating at times, produced a good working relationship.

In the spring of 1938 Ford Frick, still unsatisfied with the conditions at Doubleday Field for Major League use, directed Henry Fabian to redress deficiencies at Doubleday Field. With pressure applied, the WPA undertook the improvements in the winter of 1938 allocating $41,000 of additional funding. Nearly thirty workers toiled through the winter completing the final renovation of Doubleday Field in March 1939.

Cooperstown remained committed to a year-long celebration of the 100th birthday of baseball. Coordination of these activities was handled through the Cooperstown Baseball Centennial Committee. The Village’s plans were often disrupted by the insistence of a Major League Baseball agenda. Without Alexander Cleland’s leadership this project would have easily been unraveled. Issue after issue, Cleland stayed focused and worked through difficult situations. He had a museum to build, artifacts to collect, and had to meet security concerns of the donors. The press, though complimentary of the project, often raised issues of the authenticity of Abner Doubleday as the inventor of baseball Cleland responded to those inquiries with mixed results.

In the summer of 1938 Major League Baseball, concerned about the perception of the project. hired its own public relations men to protect and control the national image of the Baseball Centennial and established its own National Baseball Centennial Commission, incorporated in Chicago. Cleland clearly represented the Village interest versus the national interest and well represented both, but his heart was always with Stephen Clark and the Village of Cooperstown.

The museum consumed thousands of hours to seek and secure artifacts of baseball’s past and required constant communication and assurances to would-be donors of the benefits of a national baseball museum and the importance of their donations. William Beattie joined Cleland as the first curator of the museum and assumed the day-to-day activities of the museum. Beattie, well-known to the Village, was a past president of the Chamber of Commerce and an active member of the Masonic Lodge. His appointment as curator provided support and off loaded many of Cleland’s responsibilities. They worked well together to ensure the success of the National Baseball Museum. Beattie worked on displays, cataloged new acquisitions and was an active participant with all standing committees and the Cooperstown Baseball Centennial Committee. Ford Frick worked well with Beattie and enjoyed the professional approach the museum offered to its donors. As the displays were completed, the museum opened to the public in the summer of 1938 and donors were invited to see their artifacts and how they were presented. The public enthusiastically enjoyed the museum and looked forward to its dedication in 1939.

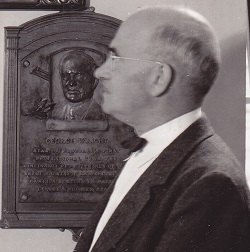

In January 1939, the National Baseball Centennial Commission outlined its marketing strategy and its commitment to an official dedication ceremony at the museum and a Cavalcade of Baseball scheduled for June 12, 1939. Bronze plaques were created and would become a prominent feature of the National Baseball Museum and Hall of Fame. Major league baseball would also support the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues’ dedication of the library and an All-Star game scheduled for July 9, 1939. This cleared the way for Cooperstown’s summer long calendar of events celebrating the Centennial of Baseball.

With Cooperstown activities scheduled, a campaign was pursued by the National Centennial Commission implemented by the public relations firm headed by Steve Hannagan. Hannagan’s story of the origin of baseball filled newspapers and publications.

The celebration would occur on sandlots and ballparks throughout the country and the world. The support of the National Centennial Commission helped cities and towns plan activities and overcome obstacles for their own celebration of the Centennial of Baseball. The emblem and its colors certainly were patriotic and many tunes Uncle Sam appeared on much of the advertising. The enthusiasm across the country was all-inclusive. Every aspect of baseball was celebrated. The country was ready for a party.

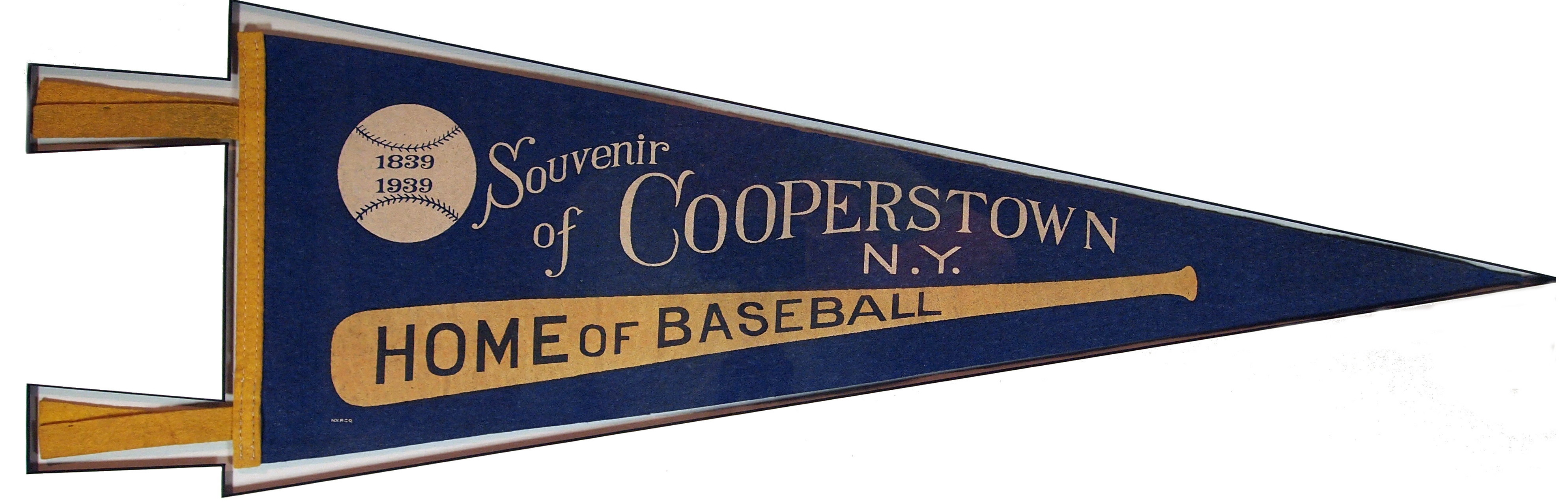

Hannagan’s campaign was so successful that day-to-day life in America was consumed by advertising and publicity of baseball activities happening in every town or region. The ephemera generated by these activities gave reason to reflect and remember special afternoons spent in the celebration of the 100th birthday of baseball. The birth story was so well presented, that although many of the press argued that Cooperstown was not the birthplace. America was ready to accept the story as the truth. The Baseball Centennial provided a welcome distraction from the Depression, the early thirties, and the war activities in Europe. Americans were feeling good for the first time in a long time and baseball, no matter where played, gave relaxation and joy.

The ephemera left behind allow us to reflect on the success of the birthday celebration and the reason they were carefully secured in the top bureau drawer or a small box in the attic.

These pennants were manufactured by the Annin Flag Company America oldest flag maker established in 1847 in New York on 16th street at Old Glory Corner.